The Apostolic writings of the New Testament were written in Greek

The preponderance of the evidence is that the New Testament manuscripts were originated in Greek with only the possible exceptions of Matthew and Hebrews.

GPT.Bible Publications available on Amazon (commissions earned, affiliate partner)

Distinguished scholar F. F. Bruce, in The Books and the Parchments

“The language most appropriate for the propagation of this message would naturally be one that was most widely known throughout all the nations, and this language lay ready to hand. It was the Greek language, which, at the time when the gospel began to be proclaimed among all the nations, was a thoroughly international language, spoken not only around the Aegean shores but all over the Eastern Mediterranean and in other areas too. Greek was no strange tongue to the apostolic church even in the days when it was confined to Jerusalem, for the membership of the primitive Jerusalem church included Greek-speaking Jews as well as Aramaic-speaking Jews. These Greek-speaking Jewish Christians (or Hellenists) are mentioned in Acts 6:1, where we read that they complained of the unequal attention paid to the widows of their group by contrast with those of the Hebrews or Aramaic-speaking Jews. To remedy this situation seven men were appointed to take charge of it, and it is noteworthy that (to judge by their names) all seven were Greek-speaking” (p.49).

~

“Paul, we may say, comes roughly half-way between the vernacular and more literary styles. The Epistle to the Hebrews and the First Epistle of Peter are true literary works, and much of their vocabulary is to be understood by the aid of a classical lexicon rather than one which draws upon non-literary sources. The Gospels contain more really vernacular Greek, as we might expect, since they report so much conversation by ordinary people. This is true even of Luke’s Gospel. Luke himself was master of a fine literary literary style, as appears from the first four verses of his Gospel, but in both Gospel and Acts he adapts his style to the characters and scenes that he portrays” (p.55-56).

New Bible Dictionary

“The language in which the New Testament documents have been preserved is the ‘common Greek’ (koine), which was the lingua franca of the Near Eastern and Mediterranean lands in Roman times” (p.713)

~

“Having thus summarized the general characteristics of New Testament Greek, we may give a brief characterization of each individual author. Mark is written in the Greek of the common man. . . . Matthew and Luke each utilize the Markan text, but each corrects his solecisims, and prunes his style . . . Matthew’s own style is less distinguished than that of Luke — he writes a grammatical Greek, sober but cultivated, yet with some marked Septuagintalisms; Luke is capable of achieving momentarily great heights of style in the Attic tradition, but lacks the power to sustain these; he lapses at length back to the style of his sources or to a very humble koine.

~

“Paul writes a forceful Greek, with noticeable developments in style between his earliest and his latest Epistles . . . . James and I Peter both show close acquaintance with classical style, although in the former some very ‘Jewish’ Greek may also be seen. The Johannine Epistles are closely similar to the Gospels in language. . . Jude and II Peter both display a highly tortuous an involved Greek. . . The Apocalypse, as we have indicated, is sui generis in language and style: its vigour, power, and success, though a tour de force, cannot be denied” (p.715-716).

~

“In summary, we may state that the Greek of the New Testament is known to us today as a language ‘understanded of the people,’ and that it was used with varying degrees of stylistic attainment, but with one impetus and vigour, to express in these documents a message which at any rate for its preachers was continuous with that of the Old Testament Scriptures — a message of a living God, concerned for man’s right relation with Himself, providing of Himself the means of reconciliation.”

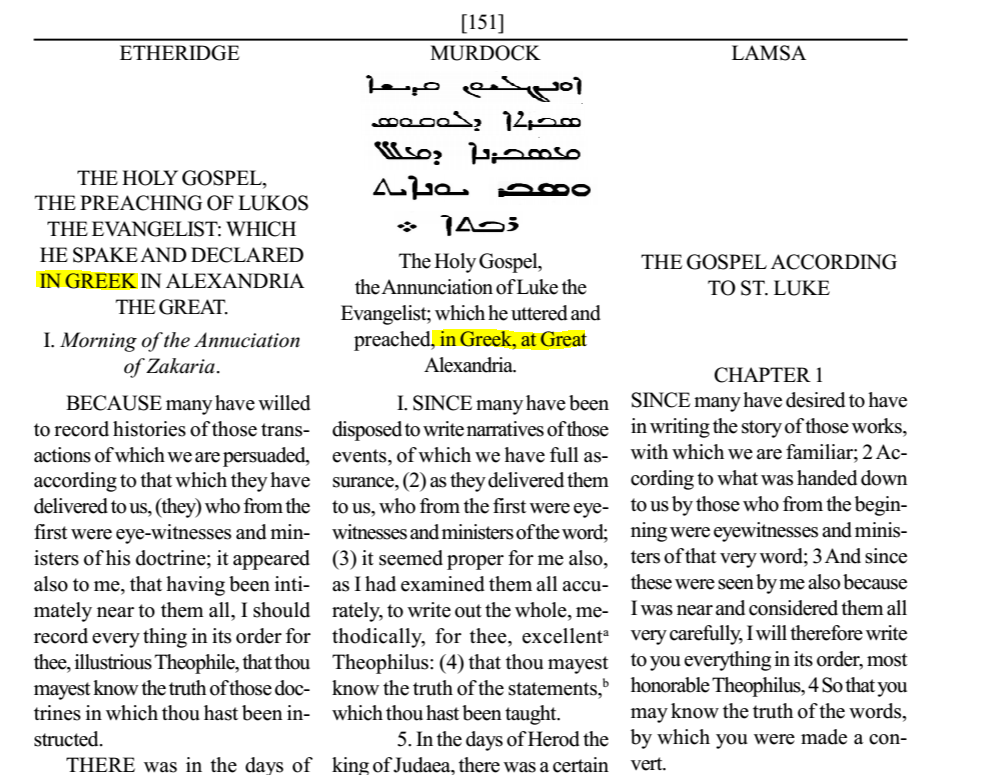

Luke-Acts was written in Greek in Alexandria

Greek texts affirm Luke was written in Alexandria (a Greek speaking region)

Early versions of the Syriac (Aramaic Peshitta) attest that Luke and acts were written in Greek at Alexandria

At least ten manuscripts of the Peshitta have colophons affirming that Luke had written his Gospel at Alexandria in Greek; similar colophons can be found in the Boharic manuscripts C1 and E1+2 which date it to the 11th or 12th year of Claudis: 51-52 A.D.[1] [2] [3]

[1] Henry Frowde, Coptic Version of the NT in the Northern Dialect, Vol. 1, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1898), liii, lxxxix

[2] Philip E. Pusey and George H. Gwilliam eds. Tetraeuangelium santum justa simplicem Syrorum versionem, (Oxford: Clarendon, 1901), p. 479

[3] Constantin von Tischendorf, Novum Testamentum Graece, Vol. 1, (Leipzing: Adof Winter, 1589) p.546

Luke was trained in Greek

Luke the physician, who wrote the gospel of Luke and the book of Acts, was a highly trained physician who evidently was trained in his craft at Alexandria, Egypt. He addresses his gospel to “most excellent Theophilus” (Luke 1:3), as he does also the book of Acts (Acts 1:1). Theophilus, is undoubtedly a Greek term. The gospel of Luke and book of Acts were undoubtedly written by Luke in the Greek language. Luke was writing primarily for the Greek-speaking, Gentile world.

St. Luke. United Kingdom: H. Frowde, 1924. Book Link

“If we turn to the secondary questions of literaly style and method of treating his topics, we cannot but be struck with the real beauty of Luke’s gospel. He has a command of good Greek not possessed by any of the other evangelists. As a specimen of pure composition, his preface is the most finished piece of writing that is to be found in the New Testament. His narrative here, and again in Acts, flows with an ease and a grace unmatched by any other New Testament historical writing. It is a curious fact that Luke, who can write the best Greek of any of the evangelists, has passages that are more Hebraistic in spirit and language than anything contained in the other gospels.”

New Bible Dictionary (p.758)

“It is generally admitted that Luke is the most literary author of the New Testament. His prologue proves that he was able to write in irreproachable, pure, literary Greek”-. He was a Gentile… From the literary style of Luke and Acts, and from the character of the contents of the books, it is clear that Luke was a well-educated Greek.”

The Latin of 1 Clement affirms the Greek of Luke

Shortly after Peter and Paul were martyred during the Neronian persecution of 65, Clement of Rome wrote his Epistle to the Corinthian church. Since he had quoted Luke 6:36-38 and 17:2 in his epistle, both the churches of Rome and Corinth must have known this Gospel by the late 60’s. Thus, the ancient Latin text of Luke provides a standard of comparison for arriving at the original Greek text of this Gospel.

Luke-Acts quotes from the Greek Septuagint Old Testament

Old Testament quotations in Luke and Acts are extensively from the Greek Septuagint.

Acts was written in Greek

Acts, who is of the same author as Luke, was written in Greek for the same reasons Luke was. References to the Hebrew language in the book of Acts essentially eliminate Hebrew as the original language for that book.

John was written in Greek in Ephesus

John was written at Ephesus (a Greek region)

Irenaeus wrote in Book 11.1.1 of Against Heresies that the apostle John had written his Gospel at Ephesus (a Greek region) and that he lived into the reign of Trajan. (98 A.D.) Ephesus was in the middle of a Greek-speaking region, and John was writing for the entire Church, not just the Jews at Jerusalem.

Eusebius quotes Irenaeus also concerning the writing of the gospels, as follows:

“Lastly, John, the disciple of the Lord, who had leant back on His breast, once more set forth the gospel, while residing at Ephesus in Asia” (p.211).

Aramaic Manuscripts attest that John wrote the Gospel in Greek while at Ephesus

The Syriac Teaching of the Apostles and subscriptions in SyP manuscripts 12, 17, 21 and 41 also stated that John wrote the Gospel in Greek while at Ephesus. The Syriac (Aramaic) version of John has numerous readings that are unsupported by any other texts.

Other Indications that John was written in Greek

John was written very late in the first century. At that time the vast majority of Christians were Greek speaking. The gospel is written in good Greek.

The majority of John’s direct quotations do not agree exactly with any known version of the Jewish scriptures.[1]

The Gospel interduces concepts from Greek philosophy such as the concept of things coming into existence through Logos. In Ancient Greek philosophy, the term logos meant the principle of cosmic reason.[2] In this sense, it was similar to the Hebrew concept of Wisdom. The Hellenistic Jewish philosopher Philo merged these two themes when he described the Logos as God’s creator of and mediator with the material world. According to Stephen Harris, the gospel adapted Philo’s description of the Logos, applying it to Jesus, the incarnation of the Logos.[3][1] Menken, M.J.J. (1996). Old Testament Quotations in the Fourth Gospel: Studies in Textual Form. Peeters Publishers. ISBN , p11-13

[2] Greene, Colin J. D. (2004). Christology in Culture Perspective: Marking Out the Horizons. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8028-2792-0., p37-

[3] Harris, Stephen L. (2006). Understanding the Bible (7th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-296548-3, p 302-310

Mark was written in Rome in the Roman tongue

Mark written in Rome for the benefit of the Roman church

According to early bishops including Papias of Hierapolis and Irenaeus of Lyon, Mark the evangelist was Peter’s interpreter at Rome. He wrote down everything which Peter taught about the Lord Jesus. At the close of the 2nd century, Clement of Alexandria wrote in his Hyptoyposes that the Romans asked Mark to “leave them a monument in writing of the doctrine” of Peter. All of these ancient authorities agreed that the Gospel of Mark was written at Rome for the benefit of the Roman church.

Mark was written in the Roman tongue was it was not Aramaic or Hebrew

SyP has a note at the end of Mark stating that it was written at Rome in the Roman tongue.[1] Bohairic manuscripts C1, D1, and E1 from northern Egypt have a similar colophon.[2] Greek Unicals G and K plus minuscule manuscripts 9. 10, 13, 105, 107, 124, 160, 161, 293, 346, 483, 484 and 543 have the footnote, “written in Roman at Rome.”[3] Greek was the primary language of Southern Italy and Sicily. Latin predominated in Rome itself. From the Epistles of both Paul and Peter, there were many in Rome where were fluent in Greek, such as Silvanus, Luke, and Timothy. It appears that Mark was serving as Peter’s into the Roman converts who spoke Greek and Latin. Most scholars believe Mark was written Greek and a few suggest it was written in Latin. What is clear as that it was not written in Hebrew or Aramaic.

[1] Philip E. Pusey and George H. Gwilliam eds. Tetraeuangelium santum justa simplicem Syrorum versionem, (Oxford: Clarendon, 1901), p314-315.

[2] (Henry Frowde, Coptic Version of the NT in the Northern Dialect, Vol. 1, (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1898), I, Ii, lxii, lxxvii)

[3] Constantin von Tischendorf, Novum Testamentum Graece, Vol. 1, (Leipzing: Adof Winter, 1589) p.325

Matthew takes from Mark (a non-Hebrew Greek source) and was written in Greek

The Gospel of Matthew was written after the Gospel of Mark was written and likely before 70 A.D. (the year of the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem). Matthew is clearly dependent on Mark for much of its content since 95% of the Gospel of Mark is found within Matthew and 53% of the text is verbatim (word-for word) from Mark. The Gospel is attributed to Matthew because of the presumption that some of the unique source material may had come from Matthew (a disciple of Jesus who was previously a tax collector) although most of the source material is from the Gospel of Mark as many see it is an embellishment upon Mark. Some scholars believe that Matthew was originally written in a Semitic language (Hebrew or Aramaic) and was later translated into Greek. It is attested by church fathers that there was an Aramaic (or Hebrew) version in addition to the Greek. Portions taken from Mark may have first been translated from Greek to Aramaic (or Hebrew). The earliest complete copy of Matthew that remains is in Greek from the fourth century.

What is clear is that Matthew is the combination of source materials rather than that of a single disciple or source. Matthew is not structured like a chronological historical narrative. Rather, Matthew has alternating blocks of teaching and blocks of activity. The attribution on the Gospel “according to Matthew” was added latter. Evidence of Church father’s attribution to Matthew extends to the second century. It has an artificial construction embodying a devised literary structure with six major blocks of teaching.

Donald Senior, The Gospel of Matthew, Abingdon Press, 1977, pg. 83

The fact that the gospel of Matthew as we now have it was evidently written in Greek, and the evidence that it used Mark as a source and may have been written in the last quarter of the first century, are all strong reasons for doubting that the Palestinian Jew and tax collector Matthew could have been its author. It would be unwise, therefore, to draw conclusions about the meaning of the gospel on the basis of its apostolic authorship alone…

Internal evidence does not lead to any more precise identification of the author of the gospel. The gospel’s rich use of Old Testament quotations and typology, its concern with Jewish issues such as interpretation of the law, its overt attempt to connect the history of Jesus with the history of Israel, and even its sharp polemic with the Jewish leaders which has the atmosphere of an internecine struggle – all of these features of the gospel suggest it was composed in Greek and its good Greek style, especially in comparison with that of its important source Mark, which Matthew often improves upon, suggest further that the author was a Hellenistic Jew, that is, one who was at home in the Greco-Roman world. … Matthew’s favorable comments about the “scribe… trained for the kingdom of heaven” (Matt 13:52) and the thoughtful, ordered nature of his gospel narrative may indicate that the evangelist was himself a Jewish scribe, that is an intelligent, educated Jewish Christian steeped in the traditions of Judaism and concerned with the interpretation of those traditions in the light of his faith in Jesus as the Messiah and the Son of God.

Theodore H. Robinson, The Gospel of Matthew, Harper and Brothers Publishers, 1927

This evangelist drew largely on a collection of Old Testament passages which were selected as being useful for apologetic purposes when arguing with Jews. Allusion has already been made to a statement attributed to Papias by Eusebius. This runs : ‘ Matthew, then, compiled the oracles (” logia “) in the Hebrew tongue. And each interpreted them as he was able ‘ (ap. Eusebius, Hist. Eccles., ill. 39)… We are left, then, with the most natural suggestion, namely, that ‘logia ‘ means the Old Testament. The work ascribed by Papias to Matthew will not have been a transcript of the whole Old Testament; that goes without saying. But it may well have been a collection of oracles ‘ dealing with the Messiah, such as might be used by the Christian to prove to the Jew that Jesus was the Christ. We know that such collections were current in the third century, and that they passed in the western church under the name of ‘ Testimonies,’ but in the Jewish church the need for them would be immediate and urgent. The best explanation of Papias’s language seems to be that Matthew prepared such a collection of ‘ Testimonies,’ using the Hebrew text, and let each person translate for himself as he had need. (page xvi-xv)

Whilst there is, of course, a great deal of Aramaic underlying our gospel, especially in the speeches and conversations, it is perfectly clear — if only from the use made of Mark — that it is not a translation from a complete Semitic original. It must have reached its present form in the Greek language. (xv)

A study of the Old Testament quotations in the gospel throws light on this remark of Papias. There are over twenty citations in those portions of Matthew which are derived from Mark, and with one possible exception (Matthew 26:31) all seem to follow the text of the LXX. An interesting case is Matthew 13:14, 15, where Mark has a loose reference, while Matthew has a complete quotation from the Greek text. Only two of these events recorded by Mark are mentioned by him as direct fulfilments of prophecy, Matthew 3:3 and Matthew 13:14, 15. Q contains barely half a dozen such quotations, and of these only those which occur in the Temptation narrative are taken from the LXX, the rest being somewhat loose references rather than direct quotations. (page xv-xvi)

Matthew inserts three quotations (all cited as fulfilled prophecy) in passages which he derives from Mark, and none of these is taken from the LXX. In Matt 8:17 and Matt 13:35 we have a completely independent rendering of the Hebrew text, and in Matt 11:5 we have a quotation which is near the LXX, but is still nearer the M.T. In passages ‘ peculiar ‘ to Matthew we have seven passages quoted as fulfilled prophecy, of which only one (Matt 1:23, emphasizing the word ‘ virgin ‘) is taken from the Greek text, and even here the wording is not identical. In the other six the quotation is either an independent translation from the M.T. or from some Hebrew text which differs from that which has become traditional. An interesting case is found in Matthew 27:9-10, which is cited as from Jeremiah, though the nearest parallel (there is no Old Testament passage with a close resemblance) is in Zechariah 11:12-13. We have thus all told a dozen passages quoted as being ‘ fulfilled ‘ in Jesus. Of these two are taken direct from Mark, and the LXX is closely followed, and in one other (possibly two others) we can observe the influence of the LXX. The rest have all been translated into Greek independently from a Hebrew text which may or may not be identical with the M.T. (page xvi)

It is impossible to avoid the conclusion that the evangelist had before him a collection of oracles originally compiled in the original Hebrew. The instance of Matthew xiii. 14-15 suggests that he himself used a Greek version by preference, and makes it probable that his ‘ oracles ‘ had already been rendered into Greek before they came into his hands. This seems to correspond fairly exactly with what we should expect if the ‘ logia ‘ of Papias were suitable proof-texts of the kind so familiar in this gospel. The fact that these ‘ logia ‘ were said to have been collected by Matthew would account for the association of the gospel in which they are most used with that apostle. The evangelist has, of course, much other material on which to draw, and for the most part it is impossible for us to trace its source. (xvi-xvii)

The Pauline Epistles were written in Greek

Paul was writing to Greek speaking Christians and churches. Koine Greek language, the common language of Greece and the former Greek empire, which had been replaced by the Roman Empire by the time of Christ. The New Testament was written in Koine Greek, and Paul wrote most of it.

The apostle Paul was the apostle to the Gentiles. He spoke Greek fluently, and used it continually as he went throughout the Roman world preaching the gospel. Only when he was in Judea, and Jerusalem, did he generally use Hebrew (Acts 22:2). In writing his epistles to the churches throughout the region — Rome, Corinth, Ephesus, Galatia, Philippi — undoubtedly he also wrote in the Greek language. There is no evidence whatsoever that he originally used Hebrew names for God instead of the Greek forms, as they have been preserved through the centuries.

The Book of Hebrews

It could be that the Book of Hebrews was initially written in Hebrew but such a version no longer remains. Eusebius reports the following claim from Clement:

Eusebius. Book 6, Chapter XIV

2. He says that the Epistle to the Hebrews is the work of Paul, and that it was written to the Hebrews in the Hebrew language; but that Luke translated it carefully and published it for the Greeks, and hence the same style of expression is found in this epistle and in the Acts. 3. But he says that the words, Paul the Apostle, were probably not prefixed, because, in sending it to the Hebrews, who were prejudiced and suspicious of him, he wisely did not wish to repel them at the very beginning by giving his name.

4. Farther on he says: “But now, as the blessed presbyter said, since the Lord being the apostle of the Almighty, was sent to the Hebrews, Paul, as sent to the Gentiles, on account of his modesty did not subscribe himself an apostle of the Hebrews, through respect for the Lord, and because being a herald and apostle of the Gentiles he wrote to the Hebrews out of his superabundance.”

What we have preserved is Hebrews in the Greek and all the OT testament references, especially the most critical ones, are from the Greek Septuagint. For example, Hebrews 1:6 quotes the Septuagint for Deuteronomy 32:43, “Let all the angels of God worship Him” – this is omitted in the Hebrew Masoretic text. Another example is Hebrews 10:38 that quotes the Greek Septuagint for Habakkuk 2:3-4, “If he shrinks (or draws back), my soul shall have no pleasure,” but the Hebrew says, “his soul is puffed up, not upright.” Another example is Hebrews 12:6 quoting the Septuagint for Proverbs 3:12, “He chastises every son whom he receives.” The Masoretic Hebrew reads “even as a father the son in whom he delights.” Using the Hebrew Masoretic rather than the Greek Septuagint would make no sense in the context of these verses. Thus it is clear that if Hebrews were to have originated in Hebrew, it would have nevertheless been quoting the Greek version of the Old Testament.

Revelation was written in Greek

A primary indication that Revelation was not written in Hebrew or Aramaic was that it was not used in the Eastern Churches in the first couple of centuries and it was excluded from the Aramaic Peshitta.

Also, Irenaeus is quoted concerning the writing of the book of Revelation, and the mysterious number “666,” the number of the Antichrist. Irenaeus writes:

“Such then is the case: this number is found in all good and early copies and confirmed by the very people who was John face to face, and reason teaches us that the number of the Beast’s name is shown according to Greek numerical usage by the letters in it. . . .” (p.211).

The New Testament primarily quotes the Septuagint (Greek Old Testament)

Of the approximately 300 Old Testament quotes in the New Testament, approximately 2/3 of them came from the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Old Testament) which included the deuterocanonical books. Examples are found in Matthew, Mark, Luke, Acts, John, Romans, 1 Corinthians, 2 Corinthians, Galatians, 2 Timothy, Hebrews and 1 Peter.

The Significance of when the books of the New Testament were written

By as early as AD 50 the vast majority of Christians were Greek-speaking, not Aramaic-speaking. If any of these books had been written before AD 40, then it more likely that they may have had an original Aramaic version, but this is not the case. It has been argued by scholars that the earliest written book of the New Testament is either Galatians or 1 Thessalonians, around AD 50. Both of these books were definitely written to primarily Greek speakers, so naturally they were in Greek. Mark may have been written in the 40s, but more likely it was in the 50s, so it is not at all surprising that it was written in Greek. 19 to 24 New Testament books were clearly written to or from Greek speaking areas.

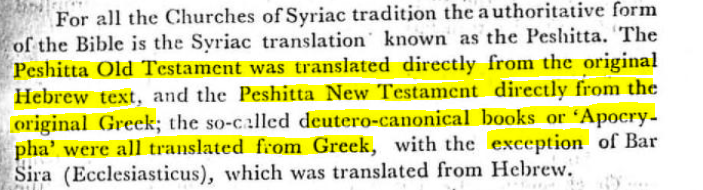

The Aramaic Peshitta NT was translated from the Greek

The New Testament of the Aramaic Peshitta was translated from the Greek manuscripts in the 5th century. The Old Syriac was translated from earlier Greek manuscripts in the 2nd century. Although the Old Syriac translation was made from a Greek text which differed from the Greek text underlying the Peshitta revision, they are translated from Greek texts. [1]

[1] Brock, The Bible In the Syriac Tradition. p13, 25-30

The Peshitta is in a dialect of Aramaic that is different than Jesus would have used. The Syriac Peshitta is not superior to the Greek manuscripts simply by virtue of being an Aramaic language.

Additional problems with Peshitta primacy are documented here: http://aramaicnt.org/articles/problems-with-peshitta-primacy/

Greek was spoken in Palestine

A reference to Greek-speaking Jews is found clearly in the book of Acts. In Acts 6:1 certain early Christians in Jerusalem are spoken of as being “Hellenists.” The King James Version says, “And in those days, when the number of the disciples was multiplied, there arose a murmuring of the Grecians (Hellenistai) against the Hebrews (Hebraioi), because their widows were neglected in the daily ministration” (Acts 6:1). The term Hellenistai applies to Greek-speaking Jews, in whose synagogues Greek was spoken, and where undoubtedly the Septuagint Scriptures were commonly used. This is verified in Acts 9:29 where we read: “And he (Saul, whose name was later changed to Paul) spake boldly in the name of the Lord Jesus, and disputed against the Grecians . . .” The “Grecians” or “Hellenists” were the Greek-speaking Jews, who had their own synagogues, even in Jerusalem.

Jesus the Messiah: A Survey of the Life of Christ, Robert H. Stein, InterVarsity Press, 1996, p.87

“The third major language spoken in Palestine was Greek. The impact of Alexander the Great’s conquests in the fourth century B.C. resulted in the Mediterranean’s being a ‘Greek sea’ in Jesus’ day. In the third century Jews in Egypt could no longer read the Scriptures in Hebrew, so they began to translated them into Greek. This famous translation became known as the Septuagint (LXX). Jesus, who was reared in ‘Galilee, of the Gentiles,’ lived only three or four miles from the thriving Greek city of Sepphoris. There may even have been times when he and his father worked in this rapidly grow- ing metropolitan city, which served as the capital city of Herod Antipas until A.D. 26, when he moved the capital to Tiberias”

Stein further tells us that the existence of “Hellenists” in the early Church (Acts 6:1-6) implies that from the beginning of the Church, there were Greek speaking Jewish Christians in the Church. The term “Hellenists” suggests their language was Greek, rather than their cultural or philosophical outlook. Remember, these were Jewish Christians whose primary language was Greek — they were not Greek philosophers or their followers, but followers of Christ Jesus.

Evidence that Jesus may have spoke Greek

There are some indications that Jesus may have spoken Greek as a second language (in addition to Aramaic).

All four Gospels depict Jesus conversing with Pontius Pilate, the Roman prefect of Judea, at the time of his trial (Mark 15:2-5; Matthew 27:11-14; Luke 23:3; John 18:33- 38). Even if we allow for obvious literary embellishment of these accounts, there can be little doubt that Jesus and Pilate did engage in some kind of conversation . . . In what language did Jesus and Pilate converse? There is no mention of an interpreter. Since there is little likelihood that Pilate, a Roman, would have been able to speak either Aramaic or Hebrew, the obvious implication is that Jesus spoke Greek at his trial before Pilate.

when Jesus conversed with the Roman centurion, a commander of a troop of Roman soldiers, the centurion most likely did not speak Aramaic or Hebrew. It is most likely that Jesus conversed with him in Greek, the common language of the time throughout the Roman empire (see Matt.8:5-13; Luke 7:2-10; John 4:46-53). A royal official of Rome, in the service of Herod Antipas, a Gentile, would most likely spoken with Jesus in Greek.

We find that Jesus journeyed to the pagan area of Tyre and Sidon, where He spoke with a Syro-Phoenician woman. The Gospel of Mark identifies this woman as Hellenes, meaning a “Greek” (Mark 7:26). The probability is, therefore, that Jesus spoke to her in Greek.

In the account in John 12, where we are told: “And there were certain Greeks among them that came up to worship at the feast: The same came therefore to Philip, which was of Bethsaida of Galilee, and desired him, saying, Sir, we would see Jesus” (John 12:20-21). These men were Greeks, and most likely spoke Greek, which Philip evidently understood, having grown up in the region of Galilee, not the back-water region many have assumed, but “Galilee of the Gentiles” (Matt 4:15) – a place of commerce and international trade, where Greek would have been the normal language of business.

Jesus the Messiah: A Survey of the Life of Christ, Robert H. Stein, InterVarsity Press, 1996, p.87

“Two of Jesus’ disciples were even known by their Greek names: Andrew and Philip. In addition, there are several incidents in Jesus’ ministry when he spoke to people who knew neither Aramaic nor Hebrew. Thus unless a translator was present (though none is ever mentioned), their conversations probably took place in the Greek language. Probably Jesus spoke Greek during the following occasions: the visit to Tyre, Sidon and the Decapolis (Mark 7:31ff), the conversation with the Syro-Phoenician woman (Mark 7:24-30; compare especially 7:26) and the trial before Pontius Pilate (Mark 15:2-15; compare also Jesus’ conversation with the ‘Greeks’ in John 12:20-36)”

Evidence from History and the Gospels that Jesus Spoke Greek

Term paper by Corey Keating

Acceptability of translating the Divine Name

A primary motivation of claiming that the New Testament was written in Hebrew by Hebrew root’s types, is the desire to insist on only using the Hebrew pronunciation of the divine name. However there is no Biblical evidence that God must be called only by His Hebrew names and titles. There is no Biblical or linguistic evidence that prohibits the use of English names and titles for God.

If Almighty God only wanted us to use the Hebrew names for God, then we would expect that the writers of the New Testament would have inserted the Hebrew names for God whenever they mentioned Him! But they do not do so. Instead, throughout the New Testament they use the Greek forms of God’s names and titles. They call God “Theos” instead of “Elohim.” They also make reference to the Greek Old Testament (Septuagint) that also uses Greek names for God.

Even if some parts of the New Testament were written in Hebrew (such as the gospel of Matthew), as some suggest, isn’t it amazing that God did not preserve those manuscripts — instead the New Testament Scriptures are preserved in the Greek language, with the Greek forms of his name and titles.

Not one book of the New Testament has been preserved in Hebrew – only in Greek. This is prima facie evidence that one language that Hebrew is not to be asserted over Greek, and that it is not wrong to use the forms of God’s name as they are translated from the Hebrew or Greek. Nowhere does the Bible tell us that it is wrong to use the names of God in Aramaic, Greek, or any other language of the earth.

It is a spurious argument to claim that the New Testament had to have been written in Hebrew, and had to contain only the Hebrew names for God. All the evidence of the manuscripts points otherwise. Those who deny that the Old Testament faithfully preserves the knowledge of God’s name, and who claim the New Testament was originally written in Hebrew, utilizing the Hebrew names for God, have no evidence or proof whatsoever to back up their claims. We should not adapt this theory when the preponderance of the evidence supports Greek authorship of the New Testament.

Peter declared: “Of a truth, I perceive that God is no respecter of persons: But in every nation he that feareth him, and worketh righteousness, is accepted with him.” (Acts 10:34-35)

Comments above adapted from ntgreek.org https://www.ntgreek.org/answers/nt_written_in_greek

The multiple pronunciations of Jesus’ name

There are some who also insist on using a Hebrew pronunciation of Yahusha for the name of Jesus since, in theory, this is how his name would pronounced in Hebrew. However in practice there is no manuscript or inscription evidence that Jesus was ever called this by Jews in early Christianity. By non-Hellenized Jews, Jesus would have been called by one of several Aramaic pronunciations such is Yeshua, Yeshu, Yishu, or Eashoa. Aramaic (similar to the Syriac of the Peshitta) was the common Semitic language of the time.

Since the early Church used the Greek and Aramaic terms for Jesus spanning across the New Testament, we should be content with them as well as to not impose a requirement that certain names can only be pronounced a certain way in a single language.

The Greek Iēsous (Ἰησοῦς) derives from an Aramaic pronunciation Eashoa (ܝܫܘܥ). To hear the Aramaic pronunciation see the video below- also at this link: https://youtu.be/lLOE8yry9Cc